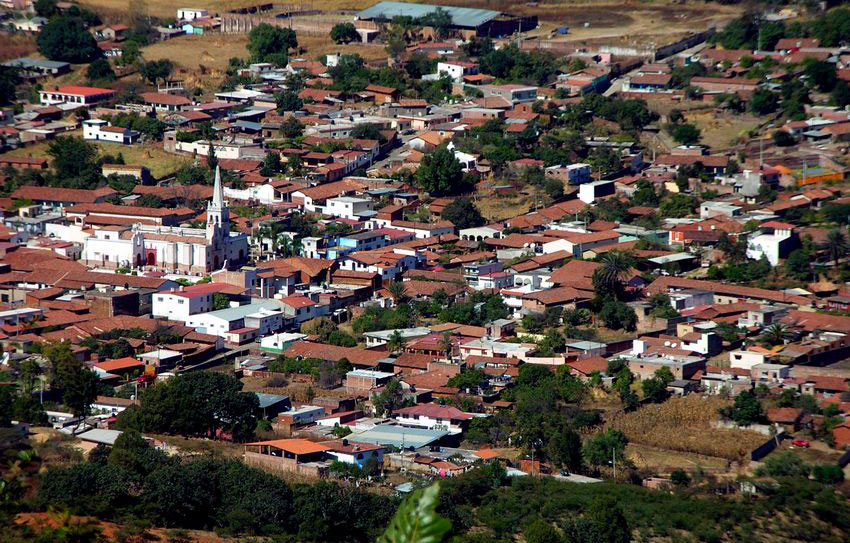

The little town of Guachinango lies hidden in the hills of the Sierra Occidental, 100 kilometers west of Guadalajara.

Mention Guachinango to most Mexicans and they will say, “Oh, yes, that delicious fish, huachinango.” Actually, the word Guachinango means “place surrounded by trees,” although today “place surrounded by mines,” might suit it better.

The rumors that occasionally reached me about this little town, however, did not refer to its mines, but to its quiet beauty. “Guachinango has the prettiest plaza in all Mexico,” I heard. And even: “Forget the Taj Mahal, you should see Guachinango’s sparkling church.”

So, one not-so-fine day during the rainy season, my wife and I drove off to see the little town, which is less than a two-hour drive from Guadalajara. We were truly impressed by the incredible beauty of that church, which is covered with hundreds of thousands of pieces of broken porcelain plates and saucers, and we were utterly charmed by the quiet beauty of the plaza.

Unfortunately, we couldn’t take pictures that day because the sky was filled with roiling black clouds and we couldn’t visit the local museum because it was a Sunday.

So, we decided to come back on a weekday in December in the morning when the sun lights up the dazzling façade of the church and takes your breath away. After enjoying the overall view, we examined the church wall up close. The shards of plates, cups and knickknacks have their own stories to tell — in Spanish, English and even Chinese!

When you step inside the church, you come upon the first clue as to how such a small community could afford such a magnificent church. The altar is covered with gold and it’s the real thing, the product of the many mines in the hills just outside town.

For a fine view of those hills, you can ascend an extremely narrow, one-person-at-a-time circular staircase — built in the 1800s — which takes you up to the bell tower where you can wander about the roof, if you dare.

As for the plaza, the flower gardens, benches and kiosks are laid out in a picture-perfect way. I’m surprised film crews are not at work in this town every day; you couldn’t ask for a better movie set.

Next we visited La Casa de Cultura, which has a large, modern museum on the upper floor. Here we discovered that the original town of Guachinango — located a few kilometers from the present site — was a well-organized indigenous community long before the Spaniards arrived. They grew corn, calabash, beans and chiles, spoke Náhuatl, had their own distinctive style of ceramics and buried their dead in deep shaft tombs.

The Spaniards arrived in 1525, but the “modern” history of Guachinango actually began in 1545 when Juan Fernández de Hijar “found a very good silver mine” in what is now the center of town and a new community gradually formed around it.

This must have been a very large mine because no sooner was it in operation than “300 indigenas and nine negroes rebelled and ran off into the hills to hide,” apparently none too happy about being enslaved. The Spaniards, of course, squelched the miners’ futile grasp at freedom and dignity.

By 1550 the Province of Guachinango had a grand total of 215 mines, including El Barqueño, which local officials say “is thought to have had the most important gold reserves in all Mexico.”

Naturally, we were now curious about Guachinango’s mines and, when we asked about them in the town hall, a young man named Nacho immediately offered to show us a few. He then recruited a friend, who in turn commandeered a truck and off we went. The first place we visited were the ruins of a big mill only five minutes from town where ore was ground into powder. These ruins are just off the highway and very easy to reach. Just follow the instructions below.

From the mill, we walked along an old track shaded by thick pines and oaks until we came to a deep, dark tunnel which disappeared into the hillside. We poked around the entrance, hoping to find a piece of gold-bearing ore, but refrained from entering the shaft as old mines are infamous for falling beams and unseen deep pits.

After that I thought we’d be heading back to town, but our enthusiastic guides said, “Oh, there’s another mine just up ahead.” That one, of course, was not far from yet another and we soon traversed half of Cerro La Catarina until at last we came to El Aguacero Mine, the site of a famous incident.

Here, in 1952, Don Salomé Hernández was working deep inside the mine, 50 meters from the entrance, when the tunnel collapsed, trapping him. During the following days, rescuers could hear him banging rocks together to indicate he was alive. After seven days, he was rescued, but emerged in very weak condition.

Legend has it that he had managed to survive all that time by eating the new leather straps he had recently attached to his huaraches. As for water, they say he had none during his entire ordeal.

On his way to the hospital in Guadalajara, according to our guides, he opened his eyes and said, “I had horrible visions there in the darkness, but I’ve been reborn . . . thank God!”

After visiting the mines, our guides drove us to the very top of Cerro La Catarina from which we could enjoy a magnificent view of Guachinango and the Sierra Occidental.

Upon our return to town, we followed our guides’ advice and went shopping first for the very tasty local bread and then for bolitas, a chewy candy made from guavas, but infinitely tastier than any other we’ve come upon — the makers say their formula is a family secret. Bolitas are available from just about any grocery store in town.

Guachinango is a bit remote, but the roads leading to it are in great shape and you’ll have no problem getting there in any sort of vehicle. Try to go in the morning to get the best view of the sparkling church facade.

To reach the center of Guachinango, ask Google Maps to take you to “Kiosco De La Plaza Civica, Guachinango.”

If you would like to visit the old mill, drive back out of Guachinango the way you came in and turn right (south) onto a dirt road two kilometers from the plaza. Follow this 330 meters and park in front of the home of Sebastián and Jesús, two old gambusinos (prospectors).

Ask them if you can visit the ruins of the Molino (mill), which lie 250 meters south of their house.

Guachinango is picturesque and historic Mexico at its best.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.

[soliloquy id="84488"]